|

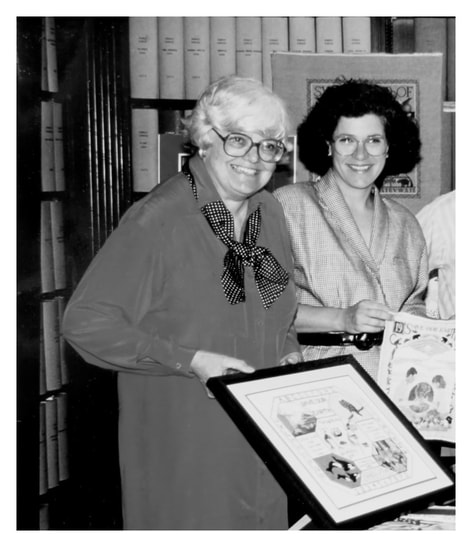

Glee Fox Krueger, 86, Scholar Sparked Interest In American Samplers Published: July 3, 2018 By Laura Beach WESTPORT, CONN. – Glee Fox Krueger, a collector and scholar of American schoolgirl needlework who left a lasting influence through her books, articles, exhibitions and lectures, died peacefully on June 17 following a long illness. Krueger was born July 3, 1931, in Chicago, to William and Matie Schlaeger. It was as a student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison that she met her future husband, Milwaukee native Ralph Krueger, whom she married in 1955. Their union lasted 63 years and produced two daughters, Whitney and Wendy. As a young wife and mother, Krueger studied Japanese flower arranging, excelled at brush painting and in the early 1960s showed Scottish terriers. Early professional endeavors included a stint working for an interior designer and a position at the Art Institute of Chicago. Krueger became interested in American antiques after Ralph’s career took the family to Connecticut. As she explained to the Northwest Sampler Guild, “I began collecting samplers in 1963 with the purchase of a boy’s sampler in a faux-grained framed from dealer Edward Grosvenor Paine of New Orleans. I had admired all the needlework in the Textile Study Room displays when I was on staff in the decorative arts department at the Art Institute.” Krueger’s passion for American schoolgirl needlework led to her friendship with the era’s preeminent collector, Theodore Kapnek. For New York’s American Folk Art Museum, she in 1978 organized an exhibition of Kapnek’s samplers and wrote its accompanying catalog, A Gallery of American Samplers: The Theodore H. Kapnek Collection. “It was the first show devoted to a sampler collection in years, and it rekindled the enthusiasm of the bicentennial,” she said later. Along with New England Samplers to 1840, published by Old Sturbridge Village, also in 1978, A Gallery of American Samplers made Krueger a nationally known expert. “To my knowledge New England Samplers to 1840 was the first regional study of American samplers. For the 1970s, it was very scholarly and showed many examples. A Gallery of American Samplers is a terrific book, still widely used and referred to,” said needlework specialist Amy Finkel of Philadelphia’s M. Finkel and Daughter. Krueger’s work paved the way for scholar-collectors such as Betty Ring, who sought to identify samplers and silk embroideries by school and teacher, superceding the chronological approach of New England Samplers to 1840. |

|

“Glee, Betty and Joan Stephens were great friends,” needlework authorities Carol and Stephen Huber, who retain Ring’s papers, wrote in an email. “They shared buckets of information. Remember, this was in the day before computers, so they traveled to find the information. They sent each other lists of girls, teachers and places they were researching and would check findings with one another.”

Krueger, a consummate researcher, told the Northwest Sampler Guild, “I’ve spent thousands of hours in libraries reading manuscripts and newspapers and have borrowed though interlibrary loan many early newspapers to read the advertisements of early American and English teachers seeking pupils. Several hundred of these were published in New England Samplers to 1840, and a few more have appeared in the Kapnek catalog.” Over the next several decades, Krueger contributed to exhibitions and publications at the Litchfield Historical Society, the Historical Society of Old Newbury and the Connecticut Historical Society, among other institutions. The CHS display, “Mary Wright Alsop, 1740-1829, and Her Needlework,” was the first focused view of one Eighteenth Century woman’s needle art, according to Whitney Krueger, noting that research was drawn from 21 linear feet of manuscripts at Yale’s Sterling Library, among other sources. Lenders included Winterthur, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Histsoric Deerfield, Middlesex County Historical Society and Yale, along with several living descendants. An accomplished lecturer and teacher, Krueger’s speaking career began around 1970 at Strawbery Banke Museum. A list of her many engagements and contributions are summarized on the Glee Krueger Collection website. One of her last professional appearances was in 2010, when she participated in a symposium at the Connecticut Historical Society in conjunction with “Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740-1840.” The exhibition’s curator, Susan P. Schoelwer, remarked, “No study of Connecticut needlework or of American samplers, generally, could be complete without reference to the pioneering scholarship of Glee Krueger. Whenever I thought I had a new idea, I found that Glee had blazed the trail, ferreting out valuable leads and primary source documentation.” To this, Elizabeth Abbe recently added, “The Connecticut Historical Society had been her home away from home, where she spent countless hours recording the name of every needlework teacher she could find from Eighteenth Century newspapers. Glee identified more than 625 schools in New England, most of which had not been known to scholars before.” As Carol and Stephen Huber concluded, “Glee was a quiet trailblazer whom many followed. She was always generous with her research. Her excitement and scholarship on the subject helped establish the market and inspire collectors. It will continue to do so long into the future.” Finkel noted, “Glee had a wonderful, soft-spoken way about her. Nonetheless, her voice carried great weight in the field. We stand on her shoulders.” Of her mother, Whitney Krueger said, “She was a dedicated researcher and writer who could never pass up an antiques shop. She will be missed by many but survived by her extensive body of work, of which she was very proud.” |